Theory

Using worked and partially completed examples

A worked example is a problem that has already been solved for the pupil, with every step fully explained and clearly shown. The beauty of a worked example is that they make visible an expert’s problem-solving solution, and then this is shared with the novice pupil as an example to learn from.

They also free up the pupil’s working memory by shifting the focus from finding the correct answer to understanding and learning the steps in the example. This means that they are more likely to recall how to solve this type of problem when they are faced with it in the future (CESE, 2018).

When you are creating a worked example, you are not aiming to reduce the complexity of the knowledge being learnt and remove any of the academic rigour around it. The knowledge will remain complex and pupils will need to partake in effortful thinking in order to understand it. But worked examples are effective at removing any extraneous information and distractions that would stop pupils being able to think deeply about each step of the process. With the support of the example they can focus instead on the content and exactly how an expert would solve it.

Effective worked examples often share the following features:

- They offer a clear structure and reasoning behind the steps shown

- They take pupils through the problem to its logical conclusion without any step being left to interpretation

- The teacher talks through their reasoning, sharing their expert thinking and understanding

- After studying a worked example, learners require practise on their own to provide them with feedback on whether they have learned it or not

Partially completed examples are worked examples that have had some steps left blank for pupils to complete. They allow the teacher to direct the pupil to where the practise needs to take place. The idea behind a partially completed example is that you are directing pupils to where you want them to focus their thinking.

Worked examples - Benjamin Riley

Listen to Ben Riley from Deans for Impact talk about why worked examples can be so effective in reducing the risk of overloading the working memory. He also talks through a worked example of how to solve a crossword puzzle, modelling how he would share his thought process aloud as he would do with his pupils.

Video transcript

Hi, I’m Benjamin Riley with Deans for Impact and in this module, I’m going to talk to you about something called a “worked example” and why it may be particularly useful to you as a teacher.

So, what is a “worked example”? Well, a worked example is just a step-by-step example of how to solve a problem. That sounds simple in concept but it’s actually kind of complex to actually use as a teacher in your classroom. So, what I thought I might do is try to explain using an example of a worked example, if you will. And I’m going to do that in an unusual context perhaps, using crossword puzzles. Now I know I just lost a few of you because a few of you hate crossword puzzles, and a few of you may actually love them and the stuff I’m about to do may be a little bit elementary to you, but I actually think crossword puzzles contain an awful lot of information about how we think that is particularly useful. And I think thinking about how to create a worked example for crossword puzzles may give you some insight into how to create worked examples for anything that you might want to teach.

So, let’s start by thinking about what isn’t a good example of a worked example around crossword puzzles. If I was going to try to teach you how to be better at solving crossword puzzles, here’s what I wouldn’t do – I wouldn’t go take a bunch of crossword puzzles, fill them all in and give them to you and say “study those”. That would be, I think, a remarkably ineffective way to help you get better at solving crossword puzzles. You would be desperately trying to memorise information, but what you wouldn’t be doing is learning a process for how to solve a crossword puzzle. And that’s something I really want to emphasise, a worked example gives you step-by-step instructions as to how you would go through and solve something. It does ultimately lead you to the answer, so it’s not as if you’re trying to hide that, but it’s about that process of cognition and thinking that gets you to where you want to go. So, that’s what we’re trying to do with a worked example. How might we actually do that in the context of solving crossword puzzles?

Well, there’s a few techniques that you might use to make the process a little bit less burdensome on your working memory, so that you can approach crossword puzzles and start to fill them in. Let’s start with the first rule:

- Fill in the blanks

You can look at all of the clues that are given for a crossword puzzle and you will see places where you have one or two words and then a blank space where you’re supposed to fill in the blank of those words. And because a lot of information’s been given to you in the clue already, those typically are the easiest sort of clues to immediately answer. So, imagine in this crossword puzzle that we’re doing, that three across says “Prime ___”. Think about what word might go in there. I think a few of you immediately thought Prime Minister, right? We’re talking in the UK, right? A few of you might be hungry, and you might have thought Prime Rib, right? And a few of you may be a bit nerdy, might be into Star Trek, might have thought Prime Directive. And who knows, maybe there are some other ‘prime’ words you thought of? But my guess is most of you are somewhere in there and that most of you were probably thinking Prime Minister. So, let’s just take a look how many letters we have for this clue. Right, it’s eight… Minister has eight… let’s go ahead and put that in. Now it’s always good in a crossword puzzle to put in with pencil, but for these purposes we’re going to feel pretty good about Prime Minister being the right answer here. Okay, so, we’ve got one technique for filling in a few of the clues, what’s another one?

Okay, so, fill in the blank is the first step in our worked example. The second step is attack the three letter clues. Three letter clues are easier to answer, often because they only have three letters, you only have to figure out which three letters fit in it. So, let’s imagine now a clue that says, “TV in the UK” and it has only three letters. You’ve got it, right? This came pretty quick? BBC? Um, again, this is why having this process will help us solve this puzzle faster and I would note too here that you can be explicit about certain things that will help students get better at things. What I mean by that is, take this clue: “TV in the UK”. You’ve got two acronyms in there. Clues that have lots of acronyms in them usually have an acronym as an answer. There’s no need to hide this from students, you can go right out and say “Hey, if the clue has an acronym, it probably has, the answer probably has an acronym as well”. That’s why explicit instruction at the beginning of working with a student or a pupil is often more effective than using an enquiry approach where they may struggle to understand what it is you want them to learn. So, lets go ahead and put BBC into our puzzle.

Alright, so we have the first two steps of our worked example for solving a crossword puzzle, let’s conclude with one last one, and I call it “looking for first letters”. So, whenever you’re doing a crossword puzzle, it’s much easier I’ve found to find the right answer to a clue if you’ve got the first letter. So, let’s imagine for a moment that in our crossword puzzle, we have an eleven-letter blank that has the clue of ‘luxurious autos’. Just think a second, what comes to mind? For many I think it’s probably Mercedes, Mercedes Benz, right? So, let’s go take a look and see if that works. Alright, Mercedes is too short, Mercedes Benz is too many letters. Alright, so we don’t have it, but now let’s imagine that we have the first letter crossing with Prime Minister so that we know the first letter of this clue is ‘R’. Luxurious autos, starting with R, anything coming to mind? Okay, you’ve got it, right? Rolls Royce’s of course! Elegant cars made in Britain? Sure, they break down a lot, but this is not meant as a commentary on British engineering. It is meant as a commentary on how to develop a step-by-step process for solving something that can be intimidating and complex and that, frankly, is what a lot of things in education appear to students – intimidating and complex. And if you as a teacher can develop a worked example to help them think through the process that they can use in order to understand and learn about something, I think you’ll put your students in a better position to be able to learn what it is you want them to learn. And I hope I’ve put you in a slightly better position in being able to solve crossword puzzles, and I hope you’ll give them a go!

So, thanks for listening and try out a worked example with your students when you get the chance.

Worked and partially completed examples in action

In this section you will hear from teachers explaining why they have found worked and partially complete examples useful for focusing pupil thinking and sharing their expert knowledge. You can also see examples of teachers using worked examples in action in their classroom. Select videos to view that are most appropriate to your phase.

Using worked examples

Hear from English Teacher Joseph Craven as he talks through how he incorporated a worked example into an end of unit lesson to support pupils to effectively answer an exam question.

Video transcript

Worked examples are a hugely important part of the learning process. They offer a model of expert thinking and processing and they demonstrate how an expert would apply their knowledge when working to answer a question.

They are also beneficial as they give the teacher an insight into their pupils’ perspective when faced with solving a new problem. It can be difficult to know how to answer a question or how to effectively break down a task if it isn’t something you’ve worked through and completed yourself. As a teacher you should be considering your pupils’ prior knowledge and then tailor the worked example to be built on this and accessible to them. There’s also the old danger of providing worked examples that aren’t replicable. There’s no end of teachers who have spent an hour writing a worked example to a question that a pupil has 20 minutes to answer, meaning that the quantity and quality of the response isn’t actually a replicable model. You will course naturally take a little longer to create the example to ensure it includes everything you want to demonstrate and to ensure it is designed in a way that will alleviate some of the load placed on the working memory. However, as the expert, it shouldn’t take you much longer to create than it would take your pupils to answer.

Worked examples can be introduced at almost any point as a learning tool, but I typically use them in English once the class are secure in all the foundational concepts and then I used the worked example as a way of demonstrating how to pull all that learning together. I like to think about them almost as an apprenticeship model:

- Here’s a beautiful example

- Here’s a master craftsman crafting a beautiful example

- Let’s work through the process of crafting a beautiful example together

- Now you create a beautiful example and I’m here to help if needed

- Now you create a beautiful example independently In the example shared below, it is important to know the class were already familiar with the topic. We’d been working on the opening of ‘An Inspector Calls’ for a few weeks, and they knew the characters, the opening of the narrative and so on. With this in mind, and a secure foundation of knowledge on which to build, I felt a worked example would help me demonstrate how they could pull all this learning together when answering an exam question.

The worked example was actually written by a very able pupil from the previous year, and expertly demonstrated the learning points I needed the class to pick up. The dissection shown underneath the example shares the focus and rationale for each step of the process. It’s structured as an effective paragraph (a clear point, valid evidence that’s embedded, explanation and analysis with a zoom in on a specific word, some technical terminology, and a link to the whole text). I talked through this with the class, sharing my thoughts on why this is such an excellent example at each stage. Following on from this, we would create a further example together, then the pupils would attempt an example independently. At this point I can see what steps in the process individuals have remembered. At other times, I’d produce the initial model myself, but I’d very much want to ensure that it’s of a practicable, replicable quality and length.

Worked example

At the beginning of the play, Priestley presents the inspector as an enigmatic, almost wilfully nondescript figure. After all, the description of him wearing a ‘plain darkish suit’ contrasts sharply with the ‘tails and white ties’ worn by the Birling men, just as the inspector’s habit of speaking ‘carefully, weightily’ contrasts with Birling’s speech-making, despite his claim that he doesn’t ‘often make speeches at you’. Priestley clearly intends the inspector to be juxtaposed with Birling. The two are both male and of an age, but their behaviour is as significantly different as their appearance – Birling is ‘heavy-looking, but it is the inspector’s ideas and language that allow him to speak ‘weightily’. There is, in addition, nothing specific about the inspector’s clothing or appearance, just as there is very little sense of personality or clarity in terms of his symbolic function at the beginning of the play, and the inspector’s speech seems direct and purposeful, unlike Birling’s long-winded and opinionated rant. Perhaps Priestley intends for the inspector to be defined through his function rather than his ego, something of which Birling seems incapable.

Exam or teacher model-response dissected

Point

At the beginning of the play, Priestley presents the inspector as an enigmatic, almost wilfully nondescript figure.

Evidence

After all, the description of him wearing a ‘plain darkish suit’ contrasts sharply with the ‘tails and white ties’ worn by the Birling men, just as the inspector’s habit of speaking ‘carefully, weightily’ contrasts with Birling’s speech-making, despite his claim that he doesn’t ‘often make speeches at you’.

Explanation/analysis

Priestley clearly intends the inspector to be juxtaposed with Birling. The two are both male and of an age, but their behaviour is as significantly different as their appearance – Birling is ‘heavy-looking, but it is the inspector’s ideas and language that allow him to speak ‘weightily’. There is, in addition, nothing specific about the inspector’s clothing or appearance, just as there is very little sense of personality or clarity in terms of his symbolic function at the beginning of the play, and the inspector’s speech seems direct and purposeful, unlike Birling’s long-winded and opinionated rant.

Link/development

Perhaps Priestley intends for the inspector to be defined through his function rather than his ego, something of which Birling seems incapable.

Using partially completed examples

Hear from Secondary Geography teacher Ashley Philipson as she explains how she used a partially completed example to support her pupils to explain the formation of coastal erosion.

Video script - Ashley Philipson talking about partially completed examples

A partially completed example is similar to a worked example, but with some information missing. It is used to help reduce cognitive load when pupils are learning new content or a new skill. It is a form of scaffolding to develop expertise as it allows the pupils to add to the answer themselves, developing the explanation of a key concept. I would use this strategy at a point in pupils’ learning where they had previously seen a fully worked example, or as a scaffold for a task.

I recently used it to support pupils in a task where the outcome was to explain the formation of erosional coastal features. At the beginning of the lesson, I verbally explained the formation of a wave cut platform and supported my explanation with photographs and relevant diagrams. I used the acronym SPED, which stands for Sequence, Process, Explanation and Description, as this helps to break the answer down into smaller components. Throughout the explanation, I checked for pupil understanding through questioning. Once I was satisfied that pupils were ready to begin, I explained the task to them.

They were given a partially completed explanation of the formation of erosional coastal features and were asked to complete it. This involved developing some points further and including additional detail that was missing. The level of detail missing varied for different pupils according to their current understanding on the topic. This ensured that pupils were able to focus their learning on key points without experiencing working memory overload. It developed pupils’ understanding as they were required to identify what was missing from the partially completed example and therefore understand what is needed to give a full geographical answer.

When planning this activity, I began by creating a good explanation that followed the structure of SPED and contained fully developed points. I then removed the information that I wanted the pupils to practise recalling. This ensured their recall focused on key learning points and skills that we had been working to develop.

To see worked and partially completed examples in action in the classroom, click on the relevant link below. When watching, consider the following questions:

- What did the teacher want the pupils to learn?

- How did the worked or partially complete example support this?

Worked and partially completed examples - Early Years

If you require an audio description over the video, please watch this version: Worked and partially completed examples – Early Years - Maria Craster at One Degree Academy [AD]

Worked and partially completed examples - Primary

In this KS2 lesson, the teacher builds on the pupils’ prior knowledge of decimals. In writing the sentence for the pupils, the teacher partially completes the example, directing pupil thinking towards the missing numbers and the relationship between them.

If you require an audio description over the video, please watch this version: Worked and partially completed examples - Primary [AD]

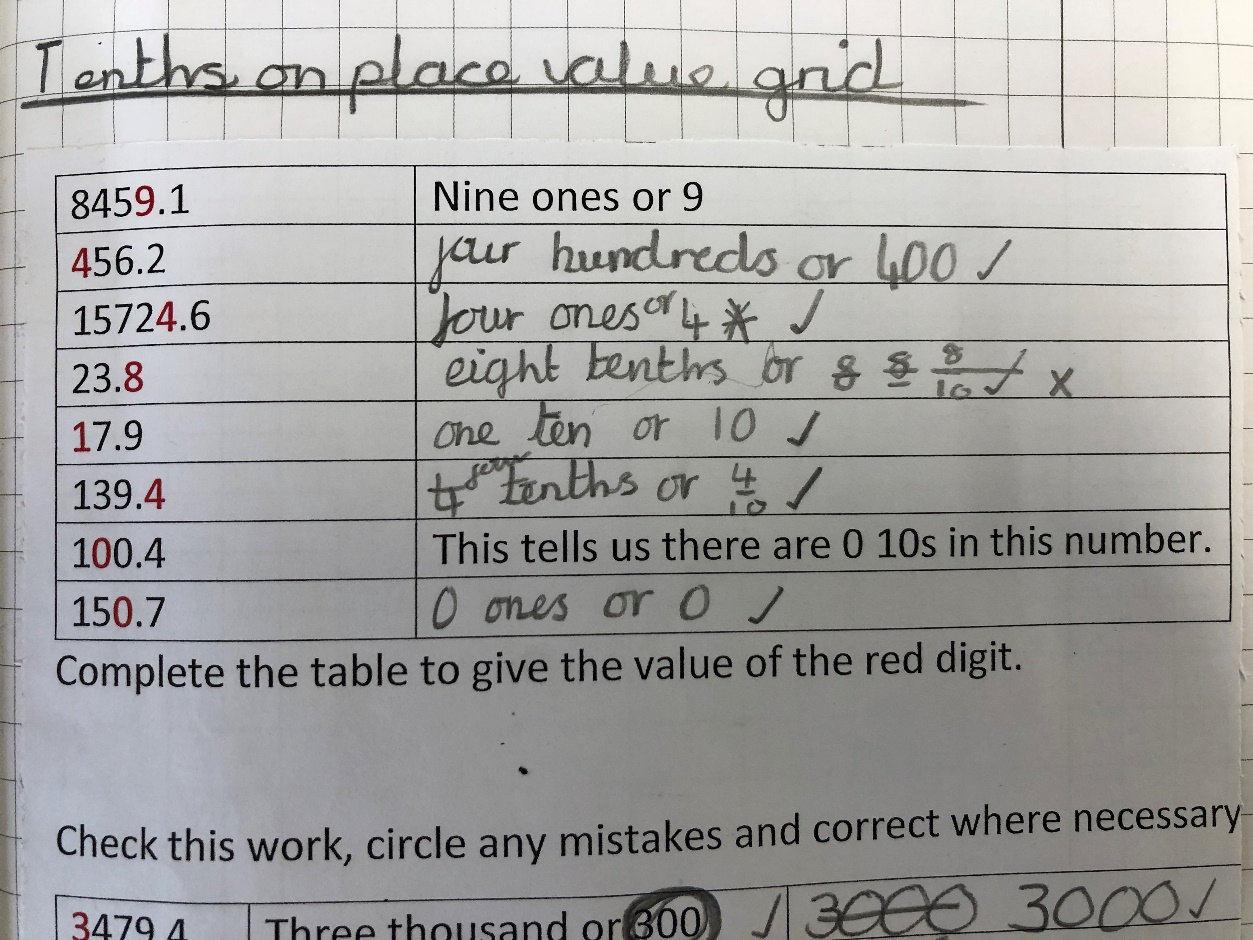

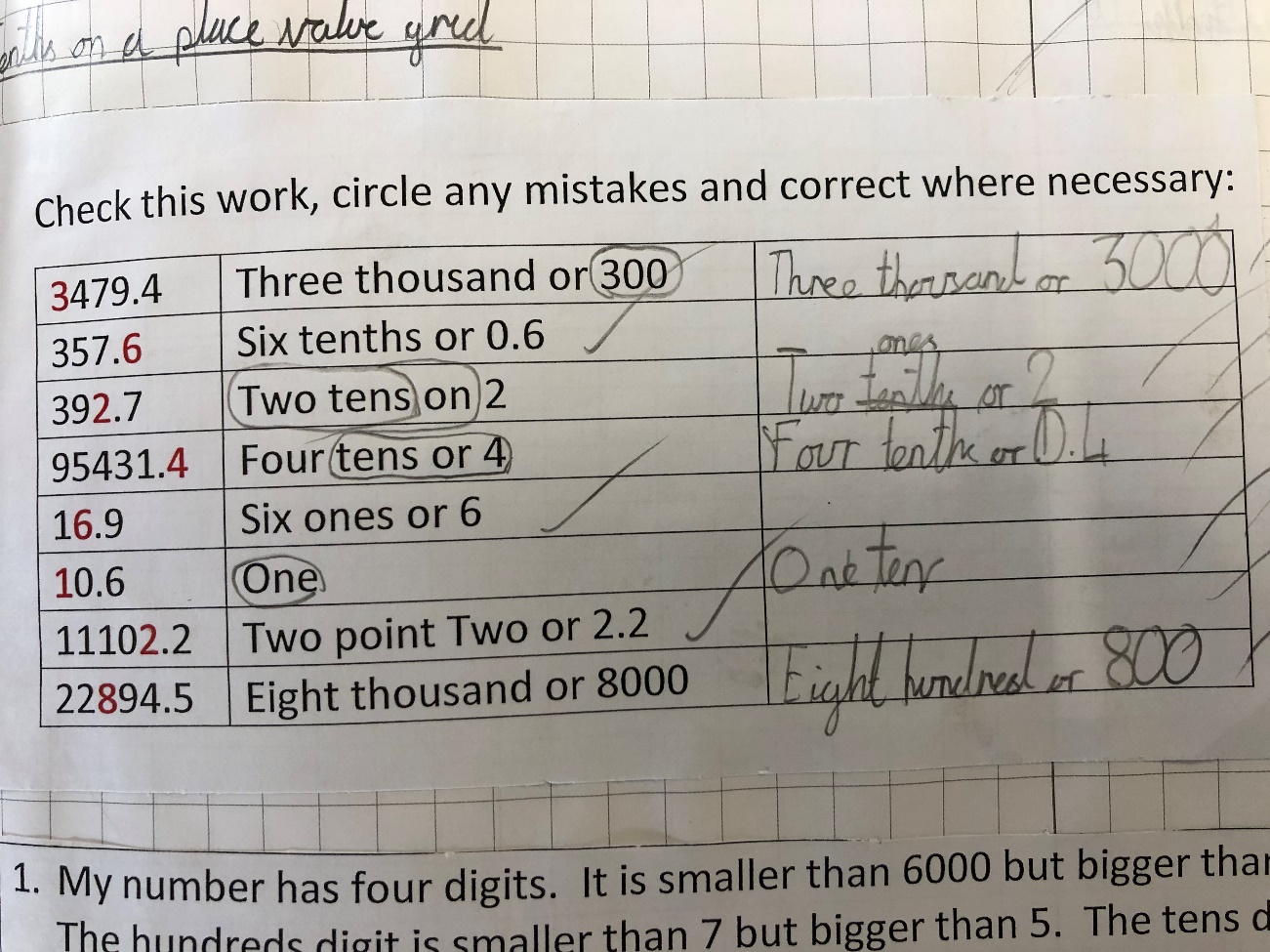

In this written exemplification, a KS2 Maths lesson incorporates a partially completed example. The teacher directs pupil thinking and addresses a common misconception.

A worked example used in year four maths

Using worked examples.

Year 4 place value lesson to include decimals (tenths). During independent work children were given the task below. The first example is completed for them. There is also another question completed further down to address possible misconceptions around asking for a value of a 0. Children could then explain that this was a place holder.

Worked examples:

Year 4 place value lesson introducing tenths. Children often enjoy looking for your mistakes and are keen to put them right. Explaining what is wrong allows them to develop skills of self-explanation which is shown to deepen understanding.

Worked and partially completed examples - Secondary

In this KS4 lesson, the teacher uses a worked example to demonstrate how to fully answer an exam question. He has created the answer himself and is now talking his pupils through it and sharing his expert reasoning.

If you require an audio description over the video, please watch this version: Worked and partially completed examples - Secondary [AD]

During your next training session, you will work with a partner to create and review a worked example for an upcoming lesson.

Activity

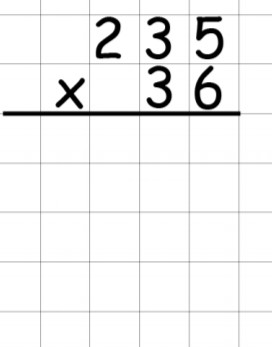

You are now going to create a worked example of your own, outlining how you would solve the math problem below.

As you do this, remember your learning from previous sessions and incorporate the following into your example:

- Break complex material into smaller steps.

- Ensure that each step removes any extraneous information and offers a clear structure and reasoning.

- Think aloud your expert reasoning in order to share this with the pupil.

Once you have completed your worked example, view a version of a worked solution to this problem.

Reflect on an upcoming lesson that would benefit from a worked example. Prepare to discuss this lesson at your upcoming training session.