Evidence

Effective teaching can transform pupils’ knowledge, capabilities and beliefs about learning

Did you realise that you, the teacher, are regarded as the biggest in-school factor which will influence your pupils’ learning and consequently their life chances?

John Hattie (2009), through a massive review of hundreds of other pieces of research, concluded that the teacher has the greatest school-based influence on pupil achievement. Effective teaching approaches can not only directly impact your pupils’ success in school (OECD, 2015) but will also have a longer-term impact on their attitude to learning throughout their lives. You can transform their knowledge, but also their belief in their own capabilities. You will learn much more about motivation and the impact of teaching on how pupils feel about learning in Block 7.

So what techniques and strategies do effective teachers use? Let’s find out.

Effective teachers introduce material in steps

In Block 2, you learned that our working memory is a short-term store for the information that you use during thought processes (Braddeley, 2003) and that our long-term memory is a vast storehouse where you retain your knowledge about the world (Willingham, 2009). Long-term memory has no known limit to its capacity.

According to education expert Barak Rosenshine, more effective teachers do not overwhelm their students by presenting too much new material at once. Rather, these teachers only present small amounts of new material at any time, and then assist the students as they practise this material. Only after the students have mastered the first step do teachers proceed to the next step.

Effective teaching could be a teacher presenting information in small sections so that pupils are more likely to understand and remember what is being taught. The teacher could introduce a small section of content, explaining the idea and modelling an example.

Then pupils independently practise a similar task with guidance and support from the teacher as required, before discussing what they have just learned and explaining it in their own words. The teacher checks for understanding, using verbal questioning or mini whiteboards. Once the teacher is happy, they move on to the next section.

Example mini lesson plan and script - Year 2

Consider the following example:

- how have they broken the content into smaller steps?

- how do they make sure that pupils master the content before moving on?

- how has the teacher built up to the more complex task of writing your own sentences?

Teaching sentence structure

Start by introducing the rules of a simple sentence.

Show a sentence on the board: ’the boy threw the ball.’

Read the sentence together.

Model aloud my thinking as I identify the subject of the paragraph

“OK so we know that a simple sentence needs to contain a verb, a subject and an object. I am going to look at the sentence here and identify these things.

"Hmmm, so I know that a verb is a doing word. So the verb in this sentence must be ‘threw’. Am I right? Yes, ‘throw’ is a doing word so that is a verb.

"I am going to circle it to show that it is the verb. Now I need to work out the subject. The subject is always the thing or person doing the verb so in this sentence the subject must be the boy because he is throwing the ball. I am going to underline ‘boy’.

"The object is the thing receiving the action so here it must be the ball. I am going to highlight ‘ball’.

“The boy threw the ball.”

Check for understanding ‒ questioning

Teacher: "Michael what three things do I need to include in my simple sentence?"

Michael: "A verb, an object and a subject."

Teacher: "Good. Paula, remind me what a verb is?"

Paula: "A doing word?"

Teacher: "Abdul, is Paula right?"

Abdul: "Yes."

Teacher: "Jakob, how do I identify the object and the subject?"

Jakob: "The subject is doing the verb and the object is receiving?"

Teacher: "Excellent."

Task 1

- Handout sheet with simple sentence examples.

- Pupils work in pairs to identify the verb, action and subject of the sentences.

- Teacher circulates, questions pupils and offers feedback.

- Pupils write own simple sentences.

- Peer assess.

- Verbally making the link: “We’re going to talk about compound sentences today. Do you remember last week when we spoke about simple sentences?”

- Demonstrating how the new idea links to previously studied material with examples: “The first step I use is to make sure my sentence is an independent clause which we practised in last week’s lesson.”

- Using “link” activities which remind pupils of the learning from previous lessons: “You are going to write four simple sentences about your trip to the zoo. First, we are going to make a bullet point list of what to include ‒ you will need 1) subject 2) verb 3) object.

- Thinking aloud whilst demonstrating how to solve a problem/complete a task. This shows pupils how experts think.

- Using worked examples – provide the solution as well as the steps taken to arrive at it.

- Showing pupils how you expect them to record and present their work.

- Demonstrating how pupils should participate in an activity or use resources.

- How does the teacher communicate how to plot points on a graph?

- How does he show his pupils what he wants them to do?

- How does he know that pupils have understood how to complete the task?

- The ideas that models are based on should be familiar to pupils, as otherwise this can confuse them further.

- It is important that pupils understand how models differ from the idea being taught and learn the underlying idea rather than the model.

- cuisenaire rods

- dienes blocks

- two fractions represented on a number line

- a quadratic function expressed algebraically or presented visually as a graph

- a probability distribution presented in a table or represented as a histogram

- As pupils enter the room, those whose names start with A‒M get a high-five and are told to take their seat.

- Ask any pupils whose names start with N–Z to stand at the back.

- Explain that it is a new school seating strategy.

- Ask other pupils: Is this fair? How does it feel to be treated this way?

- Ask pupils to take their seats and start the lesson.

- Show pupils a picture of a segregated bus in America, 1950s.

- Explain that this was a real policy and that black people were forced to ride on the back of the bus in America.

- Explain this is a type of discrimination whereby somebody is treated unfairly because of a particular characteristic – in this case the colour of their skin.

- Facilitate a discussion on types of discrimination pupils have heard about or seen and generate a class list.

- Present a newspaper report about discrimination on the board.

- Read it aloud and teacher identifies why this person has been treated unfairly and what characteristic they are being discriminated for (e.g. a woman being paid less for the same job as a man).

- Hand out newspaper clippings and pupils work in pairs to identify first whether this is discrimination and second what type of discrimination is taking place.

- Asking questions to check for understanding (“What do you understand about X?”)

- Asking pupils to summarise key points (“Can you tell me the main reasons why?”)

- Supervising pupils as they practise a new skill (“Let me watch you try.”)

- Giving immediate feedback, correcting errors (“I notice you have used X and it is resulting in Y. Try this instead.”)

- Who would benefit from resources/scaffolding, e.g. the whole class or certain individuals?

- In which part(s) of the lesson are resources required, e.g. as part of instruction/for guided practice/for independent work?

- What resources would be most appropriate and effective to facilitate learning, e.g. physical resources/written prompt/visuals?

- How and when will you withdraw the scaffolding if you need to?

- How will you assess whether continued support is needed?

- How will you ensure you don’t over-support or over-scaffold?

- How will you encourage pupils to reflect on their own learning and strengths/weaknesses?

- What scaffolds does the teacher provide?

- How effective are these in facilitating the discussion?

- In my opinion

- I think

- Firstly, secondly

- Furthermore

- For example

- In addition

- In support of this

- For instance

- On the other hand

- Consequently

- Make your argument

- Link back to the main point you made in your introductionIn conclusion…

- Alliteration

- Direct address

- Repetition

- Facts/evidence

- Emotive language

- What scaffolds does the teacher provide?

- How effective are these in supporting pupils?

- Complete a worked example on the board before setting pupils independent questions.

- Include worked examples at the start of homework or independent tasks for pupils to refer back to.

- Ask pupils to come to the board to work through an example, discussing their process as they go.

- Preparing pupils for practice – ensuring we have clearly communicated what it is we expect them to do through high-quality instructions and modelling.

- Monitoring pupils as they practise – checking for understanding and intervening where required.

- Using verbal feedback during lesson in place of written feedback after lessons where possible.

- Gradually removing scaffolding from activities and tasks so that pupils complete activities with greater independence.

- Reducing the amount of guidance provided by the teacher or other adults meaning that pupils are increasingly required to draw upon their own developing knowledge to make sense of material.

- Combining steps or teaching material in larger “chunks” so that pupils understand how ideas link together and begin to perform procedures in their entirety.

Effective teachers explicitly link new ideas to what has been previously studied and learned

Another way of reducing the load on working memory is to draw upon schemata in the long-term memory (see Block 2) as this allows information to be processed more efficiently. In other words, if pupils can draw on existing knowledge, it helps them to process new knowledge. In fact, with enough practice, schemas can “become automatic… automatic processing of schemas requires minimal working memory resources and allows problem solving to proceed with minimal effort” (Kalyuga, 2003).

As you become more experienced, you will be more easily able to link new ideas to previously studied material. This is because your knowledge of the curriculum over time will grow each year as you teach it (more on this in Block 4). You will know what you have already taught and what pupils are taught more widely in the school, meaning you can link current and upcoming learning of knowledge and skills to previous content.

An effective teacher will make this connection explicit, linking new material to what has been previously studied and learned by using some of these techniques:

Effective teachers use modelling to help pupils understand new processes and ideas

When we teach, we ask pupils to undertake tasks. These tasks should make pupils actively process (i.e. think hard about) the material. With cognitive load theory in mind, it is important that we make tasks easy to understand, so that pupils can use their processing power on the content rather than trying to work out what it is they are expected to do.

Providing models is the fourth principle in Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction (2012). Modelling means showing a pupil how to do something rather than asking them to follow instructions or find their way through a task themselves. Having a whole process modelled means that pupils can concentrate on the really important learning moments.

It is important that your model demonstrates the highest possible standard of what can be achieved and makes it accessible so pupils can reach the same standard.

Here are some ways that you might do this:

Video

Title

Modelling how to plot points on a graph, Year 5

Video type

Classroom practice

Short description

A teacher explaining to his class how to plot points on an axis

What should you focus on in this video?

Video script

Teacher: 3, 2, 1… Thank you, Year 5. Now that we can read the coordinates of points on a graph, we are going to plot some ourselves.

[Cut to shot of the board which has an empty X and Y axis. Also possible to use a visualiser instead.]

OK, who remembers the coordinates of this point in the corner where the two lines meet?

Pupil: It is zero zero.

Teacher: Yes, this is co-ordinate zero, zero and this is where you will always start from. To start, I am going to hold my pen on the coordinate zero zero like this.

[Teacher holds marker on zero zero.] The coordinate we will plot is (3, 5). Who remembers which axis the 3 tells us to move on?

Pupil: The X axis, so sideways!

Teacher: Correct. The 3 is first so it tells me to move 3 steps on the X axis. Watch carefully as I move my pen 1, 2, 3. [Teacher models jumping each step and counting out loud as they go.]

Now, I need to move 5 places in the Y axis so holding my pen really steady where I have landed I now go up for 5. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. [Teacher models pen jumping up 5 steps.] Why am I doing it this way? I know that I should use the values on the X and the Y axes as these two scales represent the values of different coordinates.

I’ve now moved 3 across and 5 up from the starting point of (0,0). This is where I draw my X. It should be in line with the number 3 on the X axis and the number 5 on the Y axis. Look at how I check by drawing an invisible line with my finger to each axis to check.

I’m going to try another one and this time, Ben I’d like you to give me the step by step instructions. How would I plot co-ordinate (4, 3)?

Ben: Right – first thing is you have to start on zero zero so put your pen there...

Effective teachers use good models which make abstract ideas concrete and accessible

What is meant by an “abstract idea”?

An abstract idea or concept is one which can be difficult to grasp.

An abstract idea is one which is removed from what you can see in front of you (a concrete idea). Some words don’t actually have a concrete equivalent ‒ e.g. bravery, power, justice or freedom. Some abstract concepts are symbolic, representing concrete things: Whilst seeing 3 coins is concrete and visible, the number 3 is an abstraction. Young children will need to learn about “threeness” from the physical world before they can use it in mathematics.

Expecting pupils to understand what an abstract idea is from its definition alone is insufficient to support their understanding. It might help pupils to understand an abstract concept through a concrete example: a beach can be used as a concrete example of the concept of erosion.

In their education, pupils will encounter many abstract ideas that pupils need to grasp. Effective teachers “use models all the time to provide a bridge between pupils’ current ideas and understanding and new understanding” (EEF, 2018). Pupils are more likely to retain knowledge if they are given multiple examples.

Models are an essential part of developing and sharing knowledge. Evidence suggests that:

The table below shows the different strategies you can use to make abstract ideas accessible.

Strategy: Using a range of examples to demonstrate the abstract idea

Example

“Here are three different examples of when someone was considered ‘brave’.”

Strategy: Facilitate discussion around an abstract idea to let pupils relate it to their own experiences

Example

“When was a time that you felt ‘free’?”

Strategy: Provide opportunities for pupils to experience an abstract concept for themselves

Example

“This morning, I am going to give all of the ‘power’ of deciding what we do in PE to you.”

Strategy: Use concrete models or examples to make abstract ideas accessible | “We are going to count out the number 12 using cubes.”

Example

“We are going to count out the number 12 using cubes.”

Strategy: Provide a graphical representation to make abstract ideas accessible

Example

“Take a look at the bar graph to compare the speed of the two cars.”

Strategy: Provide a visual example to make abstract ideas accessible

Example

“The pictures in front of you show each stage of the evaporation cycle.”

Using concrete examples to make abstract ideas accessible

How do objects help to make abstract ideas accessible?

How might this relate to your subject? Is there a physical representation of an abstract idea?

You may want to use a physical object that pupils or teachers can touch and move to support teaching and learning. These can be powerful tools for supporting pupils to engage with ideas. However, they are just tools: how they are used is important. They need to be used purposefully and appropriately in order to have an impact. Teachers should ensure that there is a clear rationale for using a concrete example to teach a specific concept. The aim is to use these to reveal structures and enable pupils to understand the subject independently.

Maths example:

Examples of different forms include:

Concrete examples in use

The teacher wants to show an abstract rule (10t – t = (10 – 1)t = 9t) through a concrete example.

A teacher said, “Give me a two-digit number ending in 0.”

A pupil said, “Forty.”

The teacher said, “I’m going to subtract the tens digit from the number: 40 – 4 gives me 36.”

The pupils tried this with other two-digit numbers ending in 0 and discovered that the result was always a multiple of 9.

The teacher said, “I’m going to use multilink cubes to see whether this will help us see why we always get a multiple of 9.”

The teacher made four sticks of 10 cubes each. “So here is 40. What does it look like if we remove 4 cubes?”

A pupil came to the front of the classroom and removed 4 cubes.

“How else could you do it?” asked the teacher.

Another pupil removed 4 cubes in a different way.

A pupil said, “Ah yes! If we take away one from each 10 then we are left with four 9s.”

Another pupil said, “And if we started with 70, we’d have 10 sevens take away 1 seven is 9 sevens.”

The teacher wrote:

40 – 4 = 10 × 4 – 1 × 4 = 9 × 4

70 – 7 = 10 × 7 – 1 × 7 = 9 × 7

The pupils discussed what was going on here, before the teacher concluded with the generalisation:

10t – t = (10 – 1)t = 9t

Reproduced from: Education Endowment Foundation (2017) Improving Mathematics in Key Stages Two and Three Guidance Report. [Online] Accessible from: Education Endowment Foundation

Using modelling to make abstract ideas accessible in Year 4

In a Year 4 lesson pupils are learning about discrimination. The teacher has planned three different ways they will model the concept of discrimination during the lesson.

How do you think this modelling will help pupils to understand what discrimination is?

How does modelling help to make an abstract idea accessible for their pupils?

Activity 1

Activity 2

Activity 3

Effective teachers use guides, scaffolds and worked examples to help pupils apply new ideas

Guidance

Pupils benefit from guidance when applying new ideas. The most effective teachers often spend longer guiding practice of new material than less effective teachers. When guided practice is too short, pupils make more errors during independent work.

Teachers can guide pupils as they rehearse new content by:

Initially this guidance is likely to come from the teacher, but our ultimate aim is for pupils to be able to practise and perform a skill independently. As pupils undertake guided practice and move towards independent practice, resources (such as graphic organisers, pictures, tables, graphs and charts) and teacher action (such as the questioning shown above) can provide them with additional support or guidance without the need to rely so heavily on the teacher. Our task is always to move them from where they are to where they need to be.

Scaffolds

The metaphor of scaffolding is derived from construction work where it represents a temporary structure that is used to erect a building. In education, scaffolding refers to support that is tailored to students’ needs.

You put up scaffolds all the time when you are teaching. Think of a time when you have asked a question, and a pupil has expressed confusion. You don’t just move on; you ask another question which re-phrases the question or you point them to a previous example which will help them. These informal teaching moments when you guide pupils through new learning are examples of scaffolding.

You can also plan scaffolds in advance of a lesson. This could be in how you present new information, breaking it down into steps as we saw earlier in this section. It could also be by providing a framework for pupils to follow, which supports them to apply a complex skill with support.

Whenever we design a task or activity, we need to consider which resources might help to purposefully scaffold pupils’ learning, whilst still ensuring they engage cognitively with the content. We can also encourage pupils to think about and explain their own levels of understanding before starting on a task. Developing pupils’ ability to reflect in this way may mean that less time needs to be spent on diagnosing who needs what support (Van de Pol et al., 2015).

You can use this series of questions to help guide your decisions:

The following examples show this in practice:

Video

Video type

Classroom practice

Short description

A Year 2 class having a discussion

What should you focus on in this video?

Video script

Teacher: OK everyone, you should now be sitting in your trios. Does everyone have a letter card, either A, B or C?

Pupils affirm, holding up their letter cards.

Teacher: Before I give you the statement, a reminder that you must use the sentence stems to structure your conversation. It starts with person A saying, “This makes me think about…”, then person B responds, “That’s interesting, I wonder if…” and person C, your sentence stem is, “Building on your points, I’m thinking about…”

Teacher: Your first statement to discuss is, “Our differences make us interesting.” OK, person A off you go.

[Pupils begin discussing. Camera pans in on one group.]

Pupil A: Emmm… this makes me think about… differences which we have from each other. Like our hair colour and our skin colour. We look different from each other.

Pupil B: That’s interesting! I wonder if we were all the same would it be fun or boring? We would be like twins so we all look the same and act the same, like robots!

Pupil C: Building on your points, I’m thinking about how it is interesting to see different people. How would your mummy know it was you if we all looked the same?

Teacher: Some really great conversations there. I liked Georgia’s question about how our mummies would recognise us if we were all the same. Let’s explore that…

You can also use resources to scaffold learning. These can include pictures, graphic organisers, charts and graphs which can all help guide pupil thinking.

Example writing frame to support KS2 persuasive writing

Title

Introduction

What is the key point you want to make? Why are you writing?

Idea 1 and three points about this. Idea 2 and three points about this. Idea 3 and three points about this.

Useful words/phrases:

In conclusion:

Techniques to use:

Video

Video type

Classroom practice

Short description

A Year 1 class drawing a dog

What should you focus on in this video?

Video script

Teacher: OK everyone, I am just going to stop you there. I can see we are finding it a bit tricky to draw a dog. I think it would help if we saw an example. Can anyone remember seeing a picture of a dog recently?

Louise: In the book we read yesterday?

Teacher: Excellent Louise. Well remembered! The books are on your table for you to use as an example. What do you notice about the picture?

Ahmed: It is a black and white spotty dog.

Teacher: Great, anything else?

Ahmed: He has two fluffy ears and four legs.

Teacher: Lovely. Loads of ideas there to include in your own picture if you would like to. Can anyone else tell me any other examples of dogs in this classroom?

Laila: The toy dog in the play area!

Teacher: Good idea! I will get the toy dog and sit him on my desk to help you. OK now we have two excellent examples to help you with your drawings. Off you go.

Worked examples

Worked examples are another great way of helping pupils to apply new ideas. You explored these in depth in Block 2 and they can be thought of as a tool for scaffolding and guiding student practice. By showing each step of a solution, you free up pupils’ working memory so that they can focus on the content and new ideas.

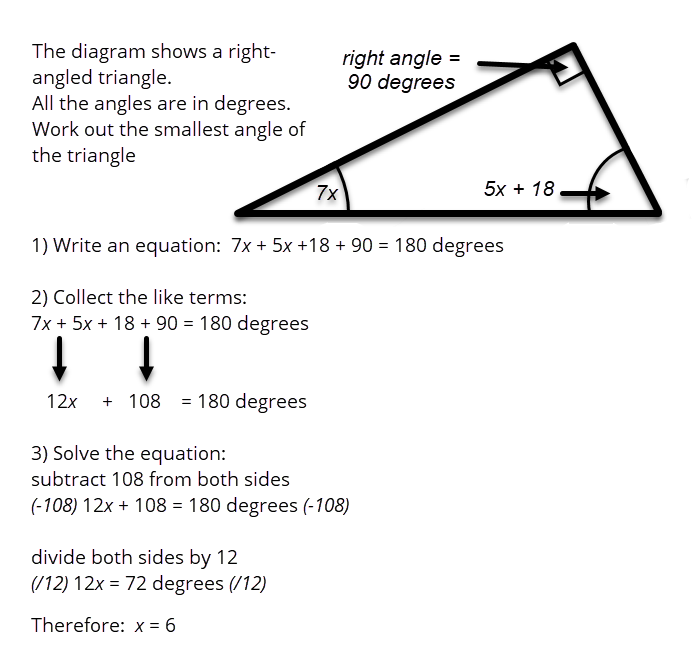

Calculating the smallest angle of a right-angled triangle

How to structure a paragraph

Key point

A key issue in our school is that in the school canteen there is the lack of seating for pupils.

Explain

The number of pupils choosing to have school lunches has increased since the quality of the food has gone up. This means that there are now too many pupils for the number of seats available and so pupils have to wait until a seat becomes available and miss out on play time.

Examples

For example, last week Year 4 were last to the lunch queue because they were getting changed after PE. The queue was so long and they had to wait until all other year groups have eaten, so they only got served and to sit down five minutes before the end of lunch! Whoever is last to lunch each day always misses out on outside time.

Link back to the question

As you can see, not having enough seating is a key issue in our school because pupils have a lot of energy at lunchtime which they need to run off outside. If all they do is queue, then they won’t work as hard when they get back into lessons!

Remember, worked examples should be planned in advance so you can be sure to explain each step in as simple and coherent a way as possible.

You could:

Effective teachers realise that practice is an integral part of effective teaching

As noted by McNamara (2010), “there is an overwhelming assumption in our educational system that the most important thing to deliver to students is content” (McNamara in Dunlosky et.al., 2013). Teachers tend to place a premium on content delivery instead of supporting pupils to practise applying new ideas effectively.

Practice is an integral part of effective teaching; ensuring pupils have repeated opportunities to practise, with appropriate guidance and support, increases success. Remember that practice is an important aspect of learning, but not all practice is equally important (Deans for Impact, 2015).

During the initial stages of learning it is vital that pupils experience success. This will be motivating and will ensure that pupils continue to try, which is the basis for deepening and extending their understanding. We can help pupils to be successful by:

Breaking a complex skill or procedure into smaller parts also enables us to pinpoint more specifically where in the process pupils are making mistakes; in isolating each step, we can identify the exact point in a process that pupils are going wrong and provide feedback at the point in time where it will make the greatest difference.

You will look at “Retrieval practice” specifically in Block 8.

Effective teachers recognise that support should be gradually removed as pupil expertise increases

The levels of support discussed above should not be maintained forever. You won’t be following your pupils into their exams or beyond the school gates, so at some point you need to begin gradually removing support.

The importance of this gradual removal of support is reinforced by the research where “strong evidence has emerged that the effectiveness of these techniques depends very much on levels of learner expertise. Instructional techniques that are highly effective with inexperienced learners can lose their effectiveness and even have negative consequences when used with more experienced learners. We call this phenomenon the expertise reversal effect” (Kalyuga, 2007).

The “guidance fading effect” tells us that novices require high levels of guidance during the early stages of learning, whereas for experts, such detailed guidance is unnecessary, or redundant, and could even be counter-productive.

As pupils develop expertise, we need to make sure we continually increase the challenge and reduce the amount of guidance we are giving them. Although we will need to fade guidance for different pupils at different rates, it is essential that all pupils reach this stage eventually.

There are a number of ways that we can fade our guidance, for example:

| Task | Increased support | Reducing support |

|---|---|---|

| Pupils need to identify metaphors and similes in a piece of text. | Pupils have a checklist to complete with definitions of metaphors and similes and one of each identified in advance. | Pupils do the task without support. |

| Pupils need to complete a piece of extended writing on the Battle of Hastings. | The teacher models “What a Good One Looks Like” on the board using a shared writing technique. Shared writing is where the teacher works with the class to produce a model version of the answer. | Pupils complete the task with the support of some sentence stems. |

| Pupils need to complete a certain number of maths problems. | The teacher and teaching assistant sit with specific groups and complete worked examples on a mini-whiteboard. | The teacher and teaching assistant circulate during the activity. |

As we have already considered, the ultimate aim is for pupils to be able to perform a skill or apply their learning independently. We need to make this aim clear to our pupils and encourage them to strive towards independence and mastery but recognising that scaffolds and supports help them on the way.

References

Coe, R., Aloisi, C., Higgins, S., & Major, L. E. (2014) What makes great teaching. Review of the underpinning research. Durham University: UK. Available at: http://bit.ly/2OvmvKO

Donker, A. S., de Boer, H., Kostons, D., Dignath van Ewijk, C. C., & van der Werf, M. P. C. (2014) Effectiveness of learning strategy instruction on academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 11, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.11.002

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013) Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Supplement, 14(1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Education Endowment Foundation (2017) Improving Mathematics in Key Stages Two and Three Guidance Report. [Online] Accessible from: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/tools/guidance-reports/

Education Endowment Foundation (2018) Sutton Trust-Education Endowment Foundation Teaching and Learning Toolkit. Accessible from: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/teaching-learning-toolkit/

Rosenshine, B. (2012) Principles of Instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00507.x

Rosenshine, B. (2012) Principles of Instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00507.

Tereshchenko, A., Francis, B., Archer, L., Hodgen, J., Mazenod, A., Taylor, B., Travers, M. C. (2018) Learners’ attitudes to mixed-attainment grouping: examining the views of students of high, middle and low attainment. Research Papers in Education, 1522, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2018.1452962.

Van de Pol, J., Volman, M., Oort, F., & Beishuizen, J. (2015) The effects of scaffolding in the classroom: support contingency and student independent working time in relation to student achievement, task effort and appreciation of support. Instructional Science, 43(5), 615‒641.

Wittwer, J., & Renkl, A. (2010) How Effective are Instructional Explanations in Example-Based Learning? A Meta-Analytic Review. Educational Psychology Review, 22(4), 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9136-5.